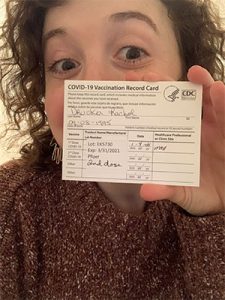

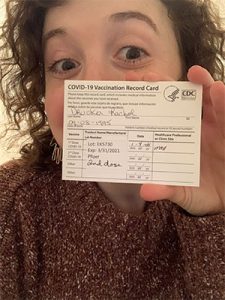

#WeLiveYes: Rachel’s COVID-19 Vaccine Journey

Getting Vaccinated for COVID-19

When I received an email inviting me to sign up for a Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine, I registered within minutes for a slot the very same day. My hands were shaking with excitement, even though I am absolutely terrified of needles. I chose to get vaccinated to protect myself as a 25-year-old immunocompromised woman with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). I chose to get vaccinated because I provide telehealth social work services to COVID-19 patients and families, and the memories of this experience will weigh heavily on me forever. I chose to get vaccinated because I spent a month visiting my father in the ICU in pre-COVID times, and I had the privilege of sitting next to him every day as he recovered from cardiac arrest, long before visitor restrictions became the new norm. Although immunocompromised people were not included in the initial vaccine clinical trials, I trust my rheumatologist, who gave me the OK to get the vaccine. I take a weekly biologic injection as well as methotrexate and prednisone, and I am aware that this means the vaccine may be slightly less effective for me. I chose to get vaccinated because I strongly believe that the benefits outweigh the risks, and I hope that you will too.

In the past few years, not a day has gone by in which I did not think about my illness. That’s sort of how it goes when you live with chronic pain, because pain does not allow you to forget. This year in particular, I am acutely aware of my identity as a young chronically ill woman, now with a new label of “high risk” of coronavirus complications. And while, this year especially, I am fortunate in many other ways — to feel economically secure, to feel safe as I walk down the street, to live without fear of losing my home — my diagnosis has profoundly affected my day-to-day life.

In the past few years, not a day has gone by in which I did not think about my illness. That’s sort of how it goes when you live with chronic pain, because pain does not allow you to forget. This year in particular, I am acutely aware of my identity as a young chronically ill woman, now with a new label of “high risk” of coronavirus complications. And while, this year especially, I am fortunate in many other ways — to feel economically secure, to feel safe as I walk down the street, to live without fear of losing my home — my diagnosis has profoundly affected my day-to-day life.

I watch people collectively commiserate about the limitations this year brought and the exhausting calculations that accompany every social interaction. Pandemic or not, though, limitations and calculations are a part of my every day. If I spend an hour cleaning, will I be able to go to the grocery store, too, or will I need to lie down and rest my knees? These are things I never had to consider before my diagnosis. And when I first encountered them, there wasn’t a globe full of people sharing my experience. It was just me, seemingly alone, figuring it all out as I went along.

For my internship for my master’s degree in social work, I work three days a week in the medical/surgical unit at Mount Auburn Hospital in Cambridge, Massachusetts. When I started in September, the hospital staff were thrilled to have zero COVID-19 patients for the first time since the start of the pandemic. Now, there are nearly 40.

In the weeks following Thanksgiving, I received three different calls from my supervisor. “Your patient’s wife/husband/child was just admitted to the hospital with COVID symptoms. You might want to check in with the family.” Although I visit in person with patients who don’t have COVID, I don’t see COVID-19 patients in person, to protect myself and conserve PPE for the medical staff who need it most. Instead, I speak to these patients and their families on the phone from my office in the hospital. About a month ago, I spoke to a woman on the phone who had three close family members hospitalized with COVID. Two of them were intubated. I wonder what kind of support will ever be enough for a family unable to visit their loved one in person. I can listen, validate their concerns, encourage the medical team to set up a Zoom call, connect them with pastoral care and so on. But I can’t change the fact that they are unable to wait in a crowded waiting room, to hold their loved one’s hand or to look the nurse in the eye. No social work class prepared me for this experience, and I’m not sure one ever could.

Soon, the day came to receive the vaccine. After the painless injection, I sat in a room for 15 minutes while a nurse observed me in case of an allergic reaction. When he asked what I was in school for, I hesitated to answer. Would he think I was taking a vaccine away from a more deserving nurse or doctor, and that social work should have been further down the list? Instead, when I explained that I’m in a dual master’s program for social work and special education, he said, “Wow, we’re lucky to have you here! I’m so glad you were able to get your shot.” When I went home that day, I experienced nothing more than a very sore arm, which frankly paled in comparison to the symptoms of RA that I deal with every day. After my second dose, I had a sore arm, a slight headache and fatigue. The next day, I felt good as new.

Share Your Story

Join a Connect Group at connectgroups.arthritis.org. And if you would like to become a volunteer or start a Connect Group, go to Volunteer with us to learn more and sign up.

When I received an email inviting me to sign up for a Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine, I registered within minutes for a slot the very same day. My hands were shaking with excitement, even though I am absolutely terrified of needles. I chose to get vaccinated to protect myself as a 25-year-old immunocompromised woman with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). I chose to get vaccinated because I provide telehealth social work services to COVID-19 patients and families, and the memories of this experience will weigh heavily on me forever. I chose to get vaccinated because I spent a month visiting my father in the ICU in pre-COVID times, and I had the privilege of sitting next to him every day as he recovered from cardiac arrest, long before visitor restrictions became the new norm. Although immunocompromised people were not included in the initial vaccine clinical trials, I trust my rheumatologist, who gave me the OK to get the vaccine. I take a weekly biologic injection as well as methotrexate and prednisone, and I am aware that this means the vaccine may be slightly less effective for me. I chose to get vaccinated because I strongly believe that the benefits outweigh the risks, and I hope that you will too.

In the past few years, not a day has gone by in which I did not think about my illness. That’s sort of how it goes when you live with chronic pain, because pain does not allow you to forget. This year in particular, I am acutely aware of my identity as a young chronically ill woman, now with a new label of “high risk” of coronavirus complications. And while, this year especially, I am fortunate in many other ways — to feel economically secure, to feel safe as I walk down the street, to live without fear of losing my home — my diagnosis has profoundly affected my day-to-day life.

In the past few years, not a day has gone by in which I did not think about my illness. That’s sort of how it goes when you live with chronic pain, because pain does not allow you to forget. This year in particular, I am acutely aware of my identity as a young chronically ill woman, now with a new label of “high risk” of coronavirus complications. And while, this year especially, I am fortunate in many other ways — to feel economically secure, to feel safe as I walk down the street, to live without fear of losing my home — my diagnosis has profoundly affected my day-to-day life.I watch people collectively commiserate about the limitations this year brought and the exhausting calculations that accompany every social interaction. Pandemic or not, though, limitations and calculations are a part of my every day. If I spend an hour cleaning, will I be able to go to the grocery store, too, or will I need to lie down and rest my knees? These are things I never had to consider before my diagnosis. And when I first encountered them, there wasn’t a globe full of people sharing my experience. It was just me, seemingly alone, figuring it all out as I went along.

For my internship for my master’s degree in social work, I work three days a week in the medical/surgical unit at Mount Auburn Hospital in Cambridge, Massachusetts. When I started in September, the hospital staff were thrilled to have zero COVID-19 patients for the first time since the start of the pandemic. Now, there are nearly 40.

In the weeks following Thanksgiving, I received three different calls from my supervisor. “Your patient’s wife/husband/child was just admitted to the hospital with COVID symptoms. You might want to check in with the family.” Although I visit in person with patients who don’t have COVID, I don’t see COVID-19 patients in person, to protect myself and conserve PPE for the medical staff who need it most. Instead, I speak to these patients and their families on the phone from my office in the hospital. About a month ago, I spoke to a woman on the phone who had three close family members hospitalized with COVID. Two of them were intubated. I wonder what kind of support will ever be enough for a family unable to visit their loved one in person. I can listen, validate their concerns, encourage the medical team to set up a Zoom call, connect them with pastoral care and so on. But I can’t change the fact that they are unable to wait in a crowded waiting room, to hold their loved one’s hand or to look the nurse in the eye. No social work class prepared me for this experience, and I’m not sure one ever could.

Soon, the day came to receive the vaccine. After the painless injection, I sat in a room for 15 minutes while a nurse observed me in case of an allergic reaction. When he asked what I was in school for, I hesitated to answer. Would he think I was taking a vaccine away from a more deserving nurse or doctor, and that social work should have been further down the list? Instead, when I explained that I’m in a dual master’s program for social work and special education, he said, “Wow, we’re lucky to have you here! I’m so glad you were able to get your shot.” When I went home that day, I experienced nothing more than a very sore arm, which frankly paled in comparison to the symptoms of RA that I deal with every day. After my second dose, I had a sore arm, a slight headache and fatigue. The next day, I felt good as new.

Although the pandemic remains far from over, those of us with arthritis know that we have to cling to moments of hope to propel us forward, to carve out space for joy in the midst of pain. I am grateful that this vaccine gives me a small glimpse of a light at the end of the tunnel and allows me to feel hopeful in a year that has felt anything but. —Rachel Drucker, graduate student in social work and special education

Share Your Story

Join a Connect Group at connectgroups.arthritis.org. And if you would like to become a volunteer or start a Connect Group, go to Volunteer with us to learn more and sign up.