Metal-on-Metal Hip Implant Risks

Learn more about the high failure rates of all-metal hip implants that may lead to additional problems such as inflammation and joint pain.

By Linda Rath

If your hip implant has been causing pain or other problems, it might be because it’s made of all metal components. Artificial hips generally last 10 to 15 years, but metal-on-metal (MoM) implants have a much shorter lifespan – failing after five years in some patients. They’re also linked to a growing list of other problems, including bone and tissue destruction and high levels of metal ions in the blood.

What Is a Metal-on-Metal Implant?

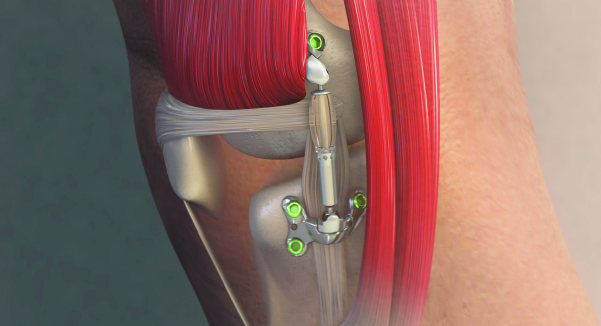

A metal-on-metal hip implant consists of a ball and cup made of a cobalt and chromium alloy. Originally developed as a more durable alternative to implants with ceramic or polyethylene (plastic) components, MoM implants proved to be the opposite. Their high failure rate is likely due to loosening, which occurs when components detach from the bone.

Debris from MoM Implants

Friction from normal wear produces particles that cause inflammation in the tissues around the joint. Over time, bone erodes and the implant loosens, leading to pain and decreased function.

All artificial hips produce some debris, but MoM implants, which have larger heads, produce more. Metal debris is also more toxic. It not only inflames and destroys tissue around the joint but also seems to damage mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in nearby bone marrow. MSCs have the ability to turn into several types of specialized cells, including bone-building cells called osteoblasts. If MSC function is impaired, new bone cells can’t form.

MoM Implant Consequences

There are a number of concerns unique to MoM implants that both patients and their doctors should be aware of.

Metal Ions in the Bloodstream

No one is sure exactly at what concentrations metal ions in the blood become dangerous, but many experts consider anything above seven parts per billion a concern. Doctors should consider testing patients with MoM hips for blood cobalt and chromium at the slightest complaint.

If the numbers are seven parts per billion or higher, your doctor may want to see you more often than once a year and may recommend an MRI to look for fluid accumulation around the joint. Some patients with high ion levels may even decide to have the implant removed.

What To Watch For

Surgeons in most countries, including the U.S., no longer use MoM implants for total hip replacement. All-metal components are still used rarely in hip resurfacing, a procedure in which the head of the thighbone is reshaped and capped with a metal covering. But that doesn’t help the estimated 1.5 million people who already have MoM or resurfaced hips.

Most experts say surgeons should see patients with all-metal devices at least annually. (If you are not sure what kind of hip implants you have, ask your doctor.) Patients should immediately report any new or worsening symptoms, including trouble walking or pain, inflammation or numbness around the hip joint.

The Food and Drug Administration, which has intensified its crackdown on metal hips, suggests that patients tell their doctors about any changes in their overall health, too, because metal ions can cause problems throughout the body.

If your hip implant has been causing pain or other problems, it might be because it’s made of all metal components. Artificial hips generally last 10 to 15 years, but metal-on-metal (MoM) implants have a much shorter lifespan – failing after five years in some patients. They’re also linked to a growing list of other problems, including bone and tissue destruction and high levels of metal ions in the blood.

What Is a Metal-on-Metal Implant?

A metal-on-metal hip implant consists of a ball and cup made of a cobalt and chromium alloy. Originally developed as a more durable alternative to implants with ceramic or polyethylene (plastic) components, MoM implants proved to be the opposite. Their high failure rate is likely due to loosening, which occurs when components detach from the bone.

Debris from MoM Implants

Friction from normal wear produces particles that cause inflammation in the tissues around the joint. Over time, bone erodes and the implant loosens, leading to pain and decreased function.

All artificial hips produce some debris, but MoM implants, which have larger heads, produce more. Metal debris is also more toxic. It not only inflames and destroys tissue around the joint but also seems to damage mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in nearby bone marrow. MSCs have the ability to turn into several types of specialized cells, including bone-building cells called osteoblasts. If MSC function is impaired, new bone cells can’t form.

MoM Implant Consequences

There are a number of concerns unique to MoM implants that both patients and their doctors should be aware of.

- Revision Surgery: When MoM hips fail – which they do at a rate six times higher than metal-on-plastic implants – the device needs to be removed and replaced with another one. This do-over – called revision surgery – is riskier, more expensive and less successful than the original hip replacement because bone loss makes the new implant harder to anchor. Some patients continue to have pain and mobility problems despite a new implant.

- Health Problems from Metal Ions: Metal-on-metal hips have raised other concerns, including potential harm from cobalt and chromium ions released into the bloodstream. These are associated with a range of potential health problems including cancer, neurological difficulties and thyroid and heart disease.

- Metal Allergy: This is a less common problem, but can cause the implant to loosen or fail, and may lead to a painful mass of soft tissue called a pseudotumor. It’s impossible to know which patients will develop an allergy to a metal hip, even if they’re known to have other metal allergies before getting the implant.

Metal Ions in the Bloodstream

No one is sure exactly at what concentrations metal ions in the blood become dangerous, but many experts consider anything above seven parts per billion a concern. Doctors should consider testing patients with MoM hips for blood cobalt and chromium at the slightest complaint.

If the numbers are seven parts per billion or higher, your doctor may want to see you more often than once a year and may recommend an MRI to look for fluid accumulation around the joint. Some patients with high ion levels may even decide to have the implant removed.

What To Watch For

Surgeons in most countries, including the U.S., no longer use MoM implants for total hip replacement. All-metal components are still used rarely in hip resurfacing, a procedure in which the head of the thighbone is reshaped and capped with a metal covering. But that doesn’t help the estimated 1.5 million people who already have MoM or resurfaced hips.

Most experts say surgeons should see patients with all-metal devices at least annually. (If you are not sure what kind of hip implants you have, ask your doctor.) Patients should immediately report any new or worsening symptoms, including trouble walking or pain, inflammation or numbness around the hip joint.

The Food and Drug Administration, which has intensified its crackdown on metal hips, suggests that patients tell their doctors about any changes in their overall health, too, because metal ions can cause problems throughout the body.

Stay in the Know. Live in the Yes.

Get involved with the arthritis community. Tell us a little about yourself and, based on your interests, you’ll receive emails packed with the latest information and resources to live your best life and connect with others.